Tulana Mahu (Shrine to Abundance)

A collaborative Art project by Tahiono Arts Collective of Niue. Created in 1999.

The Tulana Mahu is an art installation fixed inside a shipping container. It was commissioned for the 3rd Asia Pacific Biennial, Queensland Art Gallery 1999. It subsequently traveled to the Sydney Olympic Arts Festival 2000, The Cook Islands National Museum, 2002 The Manawa Art Gallery Palmerston North New Zealand, 2003.

Essay by Mark Cross, 2000

Preface

As in the tradition of the shrines of all cultures and religions, it has been a our goal to construct a sanctum of particular ambience that will give rise to a tranquil feeling allowing the participant to achieve a sense of well being, gratitude and hope. Traditionally shrines have been both religious and secular and so by combining elements of traditional Niuean culture and contemporary secular attitudes this shrine falls somewhere between these two states to which degree is dependent on the attitude of the participant. In this respect, there is a conscious attempt by the shrine’s creators to refrain from any dogmatic or didactic intent.

The Project

The Tulana Mahu was created primarily by a core group of five artists that is Al Posimani Ahi Makaea-Cross Sale Jessop Moira Enetama and myself. However nine other artists and musicians were involve directly but to a lesser degree and an important element has been the Tulana Mahu documentary by Shane Tohovaka. Various craft workers were also commissioned and other people donated a variety of items to place in the container. Since the 3rd Asia Pacific Triennial which the installation was originally created for, the added performance dimension created by Ben Tanaki and performed by family and collective members has become an important part of the project.

Ben Tanaki; Performance for the Sydney Olympic Arts Festival. Hiapo image Koren Cross

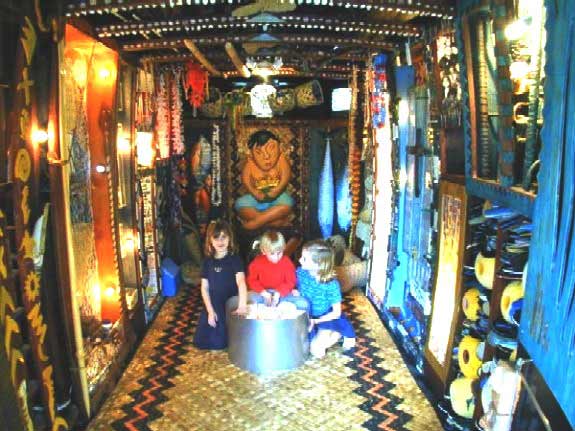

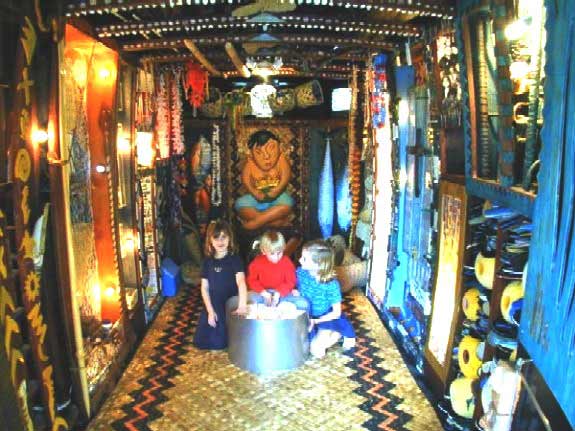

The title of our project Tulana Mahu is interpreted as Shrine to Abundance. A place where one can celebrate and give thanks for the availability of life necessities and in particular food, the shrine is divided into two sections, the outer shrine and the inner sanctuary and these are constructed respectively at the entrance and inside the regular six metre insulated shipping container. Apart from the obvious practical qualities, the container is the perfect contemporary symbol for the movement of food around the Pacific and is therefore analogous to the sustenance of the region and indeed the world.

The outer shrine and entrance area has, as a central focal point, a fabricated semi-abstract meat carcass hanging inside a aluminium frame. The insides of the entrance-way are lined with fibreglass and aluminium panels and together with the hanging carcass the minimal, sterile effect of this frontal view point contrasts dramatically with the inner sanctuary.

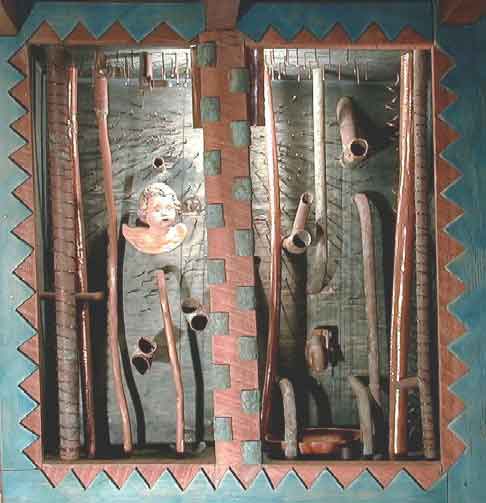

The inner sanctuary has been constructed with the Niuean fale peito, that is the external cookhouse, in mind with its central feature the umu pit or earth oven which can be found throughout the Pacific. The usual fale peito is cluttered with implements and equipment used in the procurement and processing of food as well as a huge variety of other miscellaneous paraphernalia. This conglomeration has been expressed in a huge assortment of small art and craft-works, which hang from the ceiling and are placed in a number of compartments created by constructing an irregular, decorated framework around the walls of the peito. This construction technique has suited the collaborative approach in that it has allowed a number of artists varying degrees of input. These works consist of carvings, effigies, sculptures, and utilitarian objects made of timber, weaving, bark cloth, found objects etc. and are strategically lit by low wattage lighting. At the far end of the inner sanctuary sits an effigy that represents all of the gods of Niue that have a connection with the prosperity of the island, that is to say a quintessential icon representing abundance. Above the effigy is a television monitor for the purpose of showing a continuous video containing imagery of present-day Niue and especially as it relates to the theme of food and abundance. In connection with this video montage a sound track has been created emphasising percussion and utilising the Niuean nafa drum.

Inner Sanctuary

Niue Traditions in Regards to Shrines

Owing to the rapid introduction of Christianity during the middle of the nineteenth century, information about traditional religious activities and activities pertaining to supernatural beliefs are very scant. There are a few Niuean accounts from that time however that mention the use of shrines. It is important to note that the use of incantations were much more important than visual objects in practices of worship and ceremony as can be seen in today’s Christian neo-traditional hymns. The principle god of Niue was Tangaloa in his many different forms and functions and it is also important that, quoting from the anthropologist Loeb's 1926 History and Traditions of Niue, “…the rainbow is considered in Niue as the image or abiding place of Tangaloa…” which suggests that the rainbow, which was extremely sacred, may have been a natural visual symbol of worship.

In ancient times small sacred areas were created in individual houses for the purpose of placing an idol as Loeb's informant Falani writes in 1923:

It was the custom of the people when they built a house to prepare a sacred spot in it (by spreading out a mat) and put a god on it. There were various gods, such as gods for killing children, and gods for killing fish, and gods who caused people to steal. There were so many gods that we cannot count them.

(Here Falani uses the word ‘tulana’ when referring to the sacred place and this word is now used for the pulpit of the Christian church.)

Like with Buddhism, elements of nature took on anthropomorphic qualities, but in Niue the idea that gods were associated with the myriad of natural elements went further to incorporate the foibles and qualities of humans.

Falani suggests that the so called ‘gods’ that where placed in these sacred areas were of a physical nature but it's unfortunate that he doesn't tell us what form they took or from what they were made. There are however several other accounts that mention the use of idols and it was reported to Turner in 1848 that:

A long time ago they paid religious homage to an image which had legs like a man, but in the time of a great epidemic, and thinking the sickness was caused by the idol, they broke it in pieces and threw it away. (Loeb 1926).

And Loeb also says “ The natives made an image of Huanaki out of stone at Vaihoko and have long been in the custom of “killing the god Limaua” at certain of their dances.” In fact Loeb experienced one such ceremony in 1923 where an effigy of the god Limaua was created specifically for the purpose. The purpose of this ceremony is irrelevant here but the point is that the idol was made in the form of a fabricated effigy rather than the more generically Polynesian stone or wooden carving. The fact that the idol that Falani speaks of could be ‘broken to pieces” suggests also that this was more likely to have been a constructed effigy rather than a carving.

It is important also to mention another physical object sacred in Niue even to the present day. The ‘tokamotu’ is a rainmaking fetish made from the timber of the toi tree in an elongated ovoid shape and wrapped in a piece of hiapo (tapa). About two centuries ago the tokamotu hung from the ceiling of a sacred wooden meshed fale where only chiefs were allowed to go and not without permission. It is unclear what the precise purpose of the tokamotu was but a fire was kept alight beneath it in order to keep it dry. This sacred house was believed to be the dwelling place of Tangaloa, who brought prosperity to the island and if the object were to get damp, damaged or such there would be no rain. A symbolic object, the tokamotu has been likened to the Ark of the Covenant of the Children of Israel (Smith 1904). It is believed that the tokamotu still exists buried in a cave at a place called Veve in the middle of the island.

So it can be concluded that shrines were utilised on Niue albeit mainly on a domestic basis. Where objects where worshipped on a more national level they tended to take the form of idols or talismans and did not seem to be a part of some long lasting organised religion.

Construction, Methodology and Process

To help with the understanding of the dynamics of the construction, methodology employed and creative process of the Tulana Mahu I wish to quote from William James's 1906 lecture on Pragmatism entitled "The one and the Many" when he discusses unity of purpose:

Men and nations start out with a vague notion of being rich, or great or good. Each step they make brings unforeseen chances into sight, and shuts out other vistas, and the specifications of the general purpose have to be daily changed. What is reached in the end may be better or worse than what was proposed, but it is always more complex or different.

Our different purposes are always at war with each other. Where one can't crush the other out, they compromise; and the result is again different from what anyone distinctly proposed beforehand.

From the moment of the request from Susan Cochrane for a contribution to the Shrines project arrived, a rough concept was formulating in my mind for as a year or so earlier, Niuean artist Mikoyan Vekula and I had mooted an idea based around the container format. This was to be a collaborative project between Mikoyan whose interests lay around the utilising of a variety of pan-cultural art forms for the purpose of his own Niuean oriented vision and myself whose interest was to create a pseudo museological environment commenting on global colonisation processes. The basic structure of the container interior was to be something like as we see it today with the Tulana Mahu installation. A fundamental premise of this original concept was an acute awareness of the benefit of a pragmatic approach as a reflection and influence of our isolation and this has also been an underlying but important factor in the Tulana Mahu's construction.

Because of the unavailability of Mikoyan who was then in Sydney, Al Posimani was approached for his views on the possibility of a collaborative project produced in Niue. At the time Al was working at the drawing board stage on some quite minimal ideas utilising sheet metal and casting plaster, both materials that would have to be imported to Niue. Because of this practical constraint and indeed Al's highly individual approach his participation in such a highly cooperative project was difficult to reconcile, however by laying out what we both had in mind at the time and applying a strong philosophy of pragmatism to a disjunctive proposition, a reconciling of the two approaches was established. Indeed the disjunction between the outer shrine created by Al with its emphasis on the minimal use of foreign materials and the inner sanctuary created by all the other contributors using mainly local materials (in which we include found materials of foreign origin) in great profusion, has been a key element of visual, and emotional tension within the work.

After establishing a basic plan for the inner and outer areas Sale Jessop and Moira Enetama where asked if they could contribute and Ahi Makaea-Cross was asked if a mat for the floor could be made as well as if it were possible for her as craft liaison officer to have small craft items produced for the project. Also at about this time I had talks with musicians and the broadcasting studio about the production of an audiovisual component as well as a documentary.

After things were agreed upon, the working out of the logistics and in particular the importation of the container, metal and other materials was embarked upon. I am mentioning this to give you an idea of the huge constraints and problems that have to be overcome when living in such isolation and try to explain how it affected the outcome of the finished artwork. Although our container was expected to arrive before Christmas 1998, after its frustrating non-appearance on ship after ship, it was not at our workshop until early April. Had it not arrived then on the monthly boat the project would not have proceeded and as it was, we only had three months to construct and install the interior. Apart from this there were a number of minor disasters, which were a direct result of our isolation and the inefficiency of various organisations both in Niue and New Zealand. For instance the aluminium tube that holds the carcass did arrive in Niue but was not offloaded and so it had a wonderful cruise around the Pacific and back to New Zealand before we actually received it more than two months after ordering it. But such is life in the remote Pacific and this life is reflected in the Tulana Mahu.

The late arrival of the container, which was exasperated by the fact that I was the only one able to put long hours into the project, forced us to seek the added help of some younger artists as well as volunteer workers and this impromptu employment resulted in some fresh ideas such as from young contemporaries Glen Jackson and Koren Cross. The young Reverend Matagi Vilitama who has a graphic arts background also came to our aid in the eleventh hour.

Individual Elements

I have talked about the overall concept of the shrine created in the form of a symbolic Niuean cook house, but apart from in the documentary little has been said to date about the individual components that make up the whole.

Again to help clarify I will quote from William James:

Human efforts are daily unifying the world more and more in definite systematic ways. We found colonial, postal, consular, commercial systems, all the parts of which obey definite influences that propagate themselves within the system but not to facts outside it. The result is numerous hangings together of the world's parts within the larger hangings-together, little worlds not only of discourse but of operation, within a wider universe. [and he goes on to say that]…everything that exists is influenced in some way by something else, if you can only pick the way out rightly. Loosely speaking, and in general, it may be said that all things cohere and adhere to each other somehow, and that the universe exists practically in reticulated or concatenated forms which make of it a continuous or 'integrated' affair.

In the context of the Tulana Mahu where it is seen as its own sub-universe, the individual artworks are the result of "numerous hangings-together", but are themselves the "larger hangings-together" that make up the whole installation. It could also be said that the Tulana Mahu is a part of the "numerous hangings together" that make up the "Shrines for the New Millennium" exhibition and so on and so forth.

But are the individual units of artwork integrated? The reasons for and processes of the individual works are disparate, but there is one integrating force that does unify the work into a single coherent art piece and that is the fact that its propagation was completely Niue based, albeit that many of the materials and even ideologies were imported. I have talked about the aesthetic incongruousness of the entrance carcass piece, but the paradox is that it is precisely this contrast that integrates it with the whole.

It is appropriate to start with Al Posimani's work simply because it is at the entrance. Entitled AFFCO, which is the anagram of an abattoir corporation in New Zealand, which closed down, in the late 80's, the work reflects the artist's experience in younger days while working in the South Auckland freezing works. It also pays homage to the hundreds of thousand of Polynesian immigrants that over three decades helped to build up the New Zealand economy by working as cheap labourers in abattoirs and other factory work. It is a highly appropriate statement also considering the theme of the overall artwork and especially that the medium is an insulated container, precisely the vehicle in which meat is transported to the Pacific Islands. The artist takes the carcass theme further with two further conceptual works within compartments inside the container. One is a carcass plastered with the Book of Isaia in Niuean over its whole body and the other is a kind of cage full of pig's heads. He is reluctant to have these explained.

Affco; Outer Shrine by Al Posimani, Plaster, Aluminium, Stainless Steel

Al has also been responsible for the placing of the symbolic umu pit in the centre of the interior of the container and it was because of his desire to incorporate this motif that we fell upon the idea of the cookhouse symbol. Al was born in New Zealand and went to Niue in his late twenties.

Moving into the interior on the left side there is a small work by Mikoyan Vekula who unfortunately had left prior to the construction of the installation. This small work entitled Treetat is typical of the work he was producing during his four-year stay in Niue. These were mainly pieces fabricated out of local timber on which he would 'tattoo' motifs from a variety of indigenous cultures from Native American to Celtic to Aborigine. Mikoyan emigrated from Niue when he was two and returned in his early 30's. Below this work of Mikoyan's is a set of draws that I will talk about later.

Next on the left is a mixture of art and craft work as well as some implements. A feature of this compartment is the work of folk artist Tutaue Siakifilo who is one of Niue's few carvers. Also here is a fine replica of a traditional Niuean canoe of the kind that is still used extensively. The layout of this compartment reflects the museological element that runs through the whole container which will also be talked about shortly.

The next compartment on the left has been created by Moira Enetama using local materials such as Tapa cloth, coconut leaf midribs and banyan tree bark, but it also incorporates packaging from consumer products used in Niue. The title of the work is "Can you Change me?" and she is referring to the on going force of consumer pressure placed upon her family and country. The abstract effigy motif reflect her children and thus the future, and the packaging labels, which were from the items her family consumed during June of '98, rest in the manava or the stomach of her effigy. Thus the question is asked "are we to be totally reliant on importation in the future?" Having only left Niue intermittently on various courses and seminars, Moira is the only member of the core group that has lived all her life on Niue.

Directly opposite Moira's work is an assemblage by Sale Jessop who was born in New Zealand and came to Niue in his late twenties and eventually became the high school art teacher. The assemblage consists of a beaten corrugated iron panel painted with enamel and with other found objects attached and overlaid by an ancient meat safe door. The whole assemblage is framed by discarded computer circuit boards. Sale calls the painted enamel "Metal Paleu" in reference to the ubiquitous Polynesian lavalava or rap around skirt. The patchwork qualities both reflect the techniques of the 'bush panel beaters' of Niue who cover their rusty spots with pop riveted patches as well as Sale's young days in New Zealand when his mother would patch his jeans using brightly coloured paleu material so as to create an identity/fashion statement. Sale also takes delight in exploiting the Polynesian love of kitsch and where the idea that "brighter is more" is a source of identity statement and he says "I wanted the paleu material colours to be loud and in your face fresh, [so] that it makes island spectators smile and think 'yeah that’s me' ". This and other statements by the artist suggest that his primary audience should be Polynesian which is an important issue that I will touch on later.

Besides being a ready-made mass of visual detail and busyness, the circuit boards used in framing the work have been chosen for their plastic and metallic components, which contrast nicely with the older, weathered appearance of the wood and used metal. Sale sees this as a reflection of the issue of old versus new and tradition versus tradition updated to suit a changing society. His use of the circuit boards is ironic as he has an aversion to computers and especially in their use of surveillance and the intrusion of the lives of individuals as well as their potential for the manipulation of mankind in general. Despite being brought up in a western consumer society Sale is suspicious of new technology and leans toward the old and traditional in his beliefs.

Shortly prior to creating his untitled work for the Tulana Mahu, Sale had a motorcycle accident which helped him to reestablish his traditional but somewhat neglected beliefs in Christianity but at the same time it helped him to look critically at that religion and to ascertain what it means to live, in his words "a Christ-like life" Sale's Tulana Mahu artwork was a part of this journey and therefore a potent statement about it as well as being a powerful and non didactic statement of Niuean identity in the twenty first century.

Sale Jessop

As a European, who was introduced to Niuean society during childhood, but did not go there until the age of 23, I have been less interested in identity issues directly and more interested in the change of events over the years that have lead to Niue's present cultural and environmental state. As mentioned earlier the basis of ideas for another project were transposed into the Tulana Mahu context and although they are not the focal point of the artwork, I believe the global aspect that I introduce is both pertinent and complementary to the whole.

My artwork contribution to the installation has been directed at the aspect of colonial input into Niue and especially where it has had an effect on art. To a lesser degree environmental issues have been touched upon and by taking the pragmatic approach I have been able to find ways to integrate these two issues in some works.

The particular area of interest in regards to colonial influence on Niue art was the exportation over the last century and a half of the art and artifacts of Niue and in particular the Hiapo or bark cloth which are now scattered in museums around the world. It must be said here however, that if the missionaries did not encourage these creations and they were not taken away, conditions on Niue would have prevented their existence today, but my contention is that it is the nature of colonialism to take more than it ever returns. In my opinion this inequity still exists in the pacific albeit in a different and more insidious form.

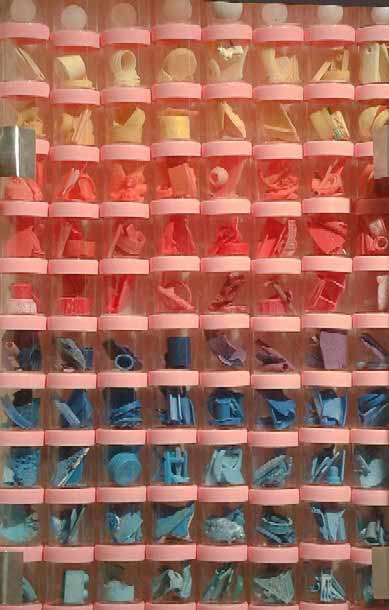

In the Tulana Mahu I addressed this in several ways. Firstly a call was made out to the global mail art network requesting small 3 dimensional items and works on paper. Works were received from places as disparate as the Czech Republic and Buenos Aries, and the works on paper were placed in the pre-mentioned purpose built chest of draws of the sort that might be found in a museum. The few three dimensional pieces were displayed in compartments further along the left-hand side of the installation. Secondly after finding an empty carton of unused urine sample jars at the rubbish dump, I when to a small remote beach and stripped it of all its plastic flotsam. Sorting them into their color categories and placing them into the jars, they were then arranged vertically in gradations across the colour spectrum and encased in a Plexiglas cabinet, again as you might find in a museum. You could say I deconstructed a beach.

The idea with both of these art works was that the imported artifacts, so to speak, symbolically replaced all of the material and intellectual property unique to Niue, which has never been replaced in kind in the past. The museological context within which the foreign treasures are placed consummates this symbolic reciprocation. The main medium of the "Flotsam work", that is the plastic detritus, provides the work with the added element of environmental concern which is also the central aspect of another piece "Shore Work". Situated on the lower right hand side of the installation, floats and thongs from the same beach have been stacked to interesting repetitive effect. Another perhaps less resolved work on the same theme is the vertical compartment on the left displaying Plexiglas encased pseudo-treasures imported by a second hand dealer in Niue.

Mark Cross; Jetsam.

Other contributions to the installation are:

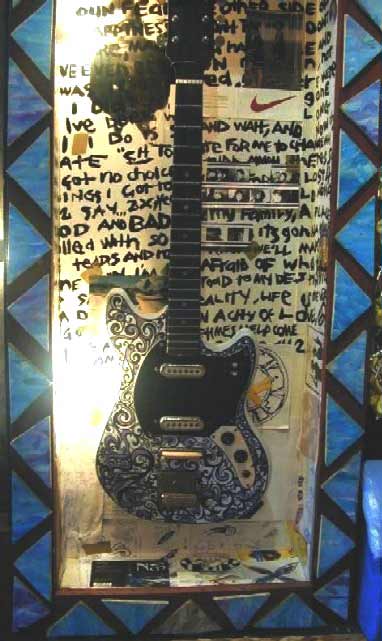

The guitar piece on the lower left hand side, by the young artist/musician Glen Jackson, reflect his strong interest in music and indeed a song that he has written which is heavily collaged with family photographs is the backdrop to the electric guitar that he has intricately decorated.

Glen Jackson

At the upper right hand side of Glen's work is a small compartment produced by the Reverend Matangi Vilitama in which he has placed an aluminium cross wrapped loosely by a piece of Hiapo inscribed with an explanation written in Niuean of the sacred Tokamotu that I have already talked about. The inference here is that the old symbol for religiosity the Tokamotu has been replaced by the new one, the Cross.

Matagi Vilitama

On the outer sides of the container are two Hiapo or barkcloth designs by Koren Cross who was flown up from New Zealand when time was running out. Koren also contributed largely to framework decoration inside the container and has two Hiapo installed in the mail art draws.

Koren Cross

Ahi Makaea-Cross created the floor mat with the help of her mother Falina. The processing of weaving materials takes many weeks and must go through up to six different stages, some off which are displayed by the semi processed pandanus in the installation. After having difficulties with its unusual shape both women took two months to complete the mat. As well as helping with the mat Falina contributed by creating the basketry in the installation.

Mat by Ahi Cross and Falina

On the upper right hand side, an assemblage entitled "Vai Fonua" or water from the land was built using copper and brass plumbing materials My original plan was to reflect the importance of water to abundance by pumping aerated water through clear piping around the ceiling of the installation and thus creating a kinetic element to the whole work. Time constraints and the possibility of technical problems because of this prevented it from eventuating and so we had to be content with the static expression of water's importance.

Vai Fonua, by Mark Cross

Again time was a factor in the outcome of the focal point of the interior the end section which has been called "Tangaloa Mahu" which is the name given to our quintessential god of abundance. Sculptured by me from a sketch by Al Posimani our effigy eventuated into something quite different to what was originally mooted. And as a whole the space took on a kitsch appearance which was perhaps due to all the spontaneous contributions that we began to receive from the public toward the end of the project's construction. With encouragement from Sale's ideas on the use of kitsch, Ahi and I began to accentuate this effect by creating the colourful fish and placing cowry shells everywhere and as a consequence this artwork was very popular in Niue.

Tagaloa Mahu; Al Posimani and Mark Cross

Popular in Niue! This brings to mind questions we had to confront when creating this artwork and still must deal with. Who is the audience for instance? Should we cater for our perception of what is required at the Asia Pacific Triennial or the Olympic Arts Festival? Or should we reflect who we are and thus seek the respect of the people of Niue? Or most interestingly, should we respond to our perception of the western perception of Polynesia? Al Posimani believes that we are catering for the latter when he wrote recently "Tulana Mahu is a gift wrapped souvenir from Niue". But in saying this he misses the irony that is expressed in Sale's work, the "Tangaloa Mahu" focal point and most contentiously Bozwell Haiosi's audio visual piece and disregards the sense of social responsibility ingrained in the cultural fabric of Niue. The most popular of urban Polynesian artists are the ones that confront and attack there own people, because this gives their supporters, middle class Europeans, what William James calls, a moral holiday and they are able to sit back and say "See we were right all along, even their own people say they are savages".

Bozwell's 20 minute video was controversial because it was heavy on sentimentality and depicted the happy islander as seen in tourism brochures. It is easy enough to say that he was responding to his perception of the western perception of what Polynesia is, but it is far more complex that this. While working with Bozwell on the editing of the video I did comment on the cliché of our noble warrior dancing in the sunset and he simply said, "who are we doing this for Mark them or us. Our warrior might be a cliché but he represents us anyway, so what!".I remained dubious until several months ago when our warrior, Tukilangi, won a gold medal in the body building section of the South Pacific Games which I thought was all very nice, but when a national holiday with parades and great fanfare were arranged in his honour, I understood completely. The final criticism lies within ourselves and all else is inconsequential. James is relevant once more here when he says "Pragmatism is prepared to take anything, to follow either logic or the senses, and to count the humblest and most personal experiences. She will count mystical experiences if they have practical consequences. She will take a god who lives in the very dirt of private fact - if that should seem a likely place to find him" or in our case if hackneyed ideas make us feel good about ourselves then hackneyed ideas have a practical and positive outcome.

But I don't want to end with a century old philosophy. We are now and Ben Tanaki's chant, which encompasses the whole meaning of the Tulana Mahu, when translated into English, makes a perfect finale to my words.

Oh Tulana Mahu e!

Oh Tulana Mahu e!

Oh Tulana Mahu e!

Who stood squattingly alone

In the wind that comes and goes

From Motusefua where I come from

My forever dwelling place

I will place my Tokamotu gently

Under a gentle warming fire

And I will slant my direction to the horizon

Where the not yet visible moon is suspended

To caress the rain nest of the sky

To frequent me a huge sprinkle

And my land would blossom abundantly

Trees will bear fruit

Food will be abundant

A large school of fish a far

Will race to the shore in scores

And my land would blossom abundantly

Call to him to bring my Katuloga

And bring my Katuhika

For I will rub for fire sparks

Of which the 'flame' would proceed forth

Oh Spark fire Spark!

Oh Spark fire Spark!

Please bring the fire sparks

Take it all fire

Take it all fire

Take it all for yourself oh fire

And forth proceed my fire

There's the fire now

For which I will cook my daily food

At the Peito my cooking place

The firewood burnt

The stones will turn red hot

I will cover my Umu properly

So my food will properly cook

And my food will properly cook

Bibliography:

Loeb: History and Traditions of Niue, Bishop Museum Press

William James: Pragmatism, Dover thrift editions

Sale Jessop: Quotes from the artist's notes 2000